Young people are more susceptible to the harmful effects of substance use due to neurocognitive sensitivities. When initiating drug use at an early age, young people are at increased risk for a more rapid transition to substance use disorder compared to adults. Identifying risk for developing substance use disorder among individuals who use drugs can inform screening, prevention, and treatment. This study used a national sample to examine risk and whether adolescents (aged 12-17) have faster or slower progression for different types of substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, opioid use disorder) than young adults (aged 18-25).

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Young people are more susceptible to the harmful effects of substance use, such as faster transition to substance use disorder, and adolescents and young adults are more likely to use these substances than adults over the age of 25. Even though substance use rates have remained relatively stable over time for youth and young adults (ages 12-25), of concern is that drug overdose deaths are on the rise in this at-risk group. While there is some degree of health and psychosocial risk for consequences for all young people who use alcohol and other drugs (e.g., cannabis, opioids, stimulants, etc.), only a subset will go on to meet criteria for substance use disorder with important differences by type of substance. For example, it is estimated that roughly 10% of cannabis users will go on to develop a cannabis use disorder in their lifetime whereas an estimated 23-38% of new heroin users will meet criteria for a heroin use disorder within 12 months. It has also been shown that earlier age of drug initiation is associated with faster transition to a substance use disorder. For instance, among recent cannabis or alcohol users in a nationally-representative sample, adolescents were more likely to have an alcohol or cannabis use disorder compared with young adults.

In the current study, Volkow and colleagues estimated the overall prevalence of different types of substance use disorders among young people reporting lifetime substance use to see if there was a faster transition to developing a substance use disorder with younger age of drug initiation. Establishing the vulnerability of young people to developing specific types of substance use disorders and developing a better understanding of which types of substances are associated with a faster transition to these disorders can lead to more effective prevention, early intervention, and treatment strategies.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This study was a secondary analysis of nationally-representative US survey data to examine the prevalence of specific types of substance use disorders by the length of time since first substance use among young people in the United States and compared the rate of this transition between adolescents (aged 12-17) and young adults (aged 18-25).

The researchers pooled together four years of data from the 2015-2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which is an annual survey that serves as the primary source for estimating the prevalence and trends of substance use, persons with substance use disorders, and treatment use in the United States. A field interviewer conducts an in-person interview with the study participant and utilizes computer-assisted technology to ensure confidentiality and decrease social desirability bias for sensitive topics. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health is a cross-sectional survey, meaning that it is done at one point in time and new study participants are interviewed each year. This survey is also a nationally-representative, meaning that a complex sampling method is used so that the approximately 65,000 people that are interviewed each year are representative of the entire non-institutionalized population of the United States aged 12 and older. Adolescents, defined as those aged 12-17, and young adults, defined as those aged 18-25, are oversampled to ensure that national prevalence estimates for these age groups are more precise.

The primary measures used in this study are age of the study participant, lifetime substance use, past-year substance use, age of initiation of substance use, and DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorder. Of note, DSM-IV diagnoses for substance use disorder comprise both “substance abuse” (meeting 1 or more of 4 criteria) and “substance dependence” (meeting 3 or more of 7 criteria). The diagnostic rules have since changed for the current version of the DSM, the DSM-5, such that substance use disorder comprises a single diagnosis with mild (2-3 criteria met), moderate (4-5 criteria met), and severe (6+ criteria met) qualifiers. The types of substance use and misuse measured are tobacco use, alcohol use, cannabis use, cocaine use, methamphetamine use, heroin use, prescription opioid misuse, prescription stimulant misuse (e.g., dextroamphetamine often referred to by the brand name “Adderall”), and prescription tranquilizer misuse (e.g., benzodiazepines like alprazolam often referred to by the brand name “Xanax”).

Researchers broke up young people into two groups based on age: adolescents 12-17 and young adults 18-25. Among individuals reporting lifetime use of a substance, they calculated the percentage of those meeting criteria for substance use disorder for that specific substance stratified across four time periods: less than 12 months, 12-24 months, 24-36 months, and greater than 36 months. To calculate these time periods, researchers took the age of the study participant at the time they completed the annual survey and subtracted it from the age that the study participant first reported using the substance. For all alcohol and other drugs, individuals meeting criteria for either DSM IV “substance abuse” or “substance dependence” were defined as having “substance use disorder.” For tobacco, the research team only examined nicotine dependence as there is no corresponding nicotine abuse diagnosis. They used a statistical technique common in survey research to account for the method that resulted in the nationally representative sample.

Demographics of the study participants were not reported but multivariable logistic regression was used to adjust for differences between the adolescent group and the young adult group as well as for variation within each group. By using this statistical technique to control for confounding, the researchers were able to estimate an adjusted percentage (i.e., rate) of individuals with a specific type of substance use disorder among those who reported lifetime use of that substance. The confounders that were controlled for included age, sex, race-ethnicity, family income, age at first substance use, the presence of specific types of substance use disorders, and the presence of a major depressive episode in the past year.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Substance use prevalence was generally higher for young adults.

The prevalence of lifetime use of alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco was 80%, 52%, and 55% respectively among young adults, and 26%, 15%, and 13% among adolescents. Prevalence of lifetime prescription drug misuse was 26% for young adults and 9% for adolescents. The prevalence of lifetime use of cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin was 11.4%, 2.5%, and 1.3% respectively among young adults, with prevalence among adolescents not estimated because of a very small sample size reporting the use of these substances.

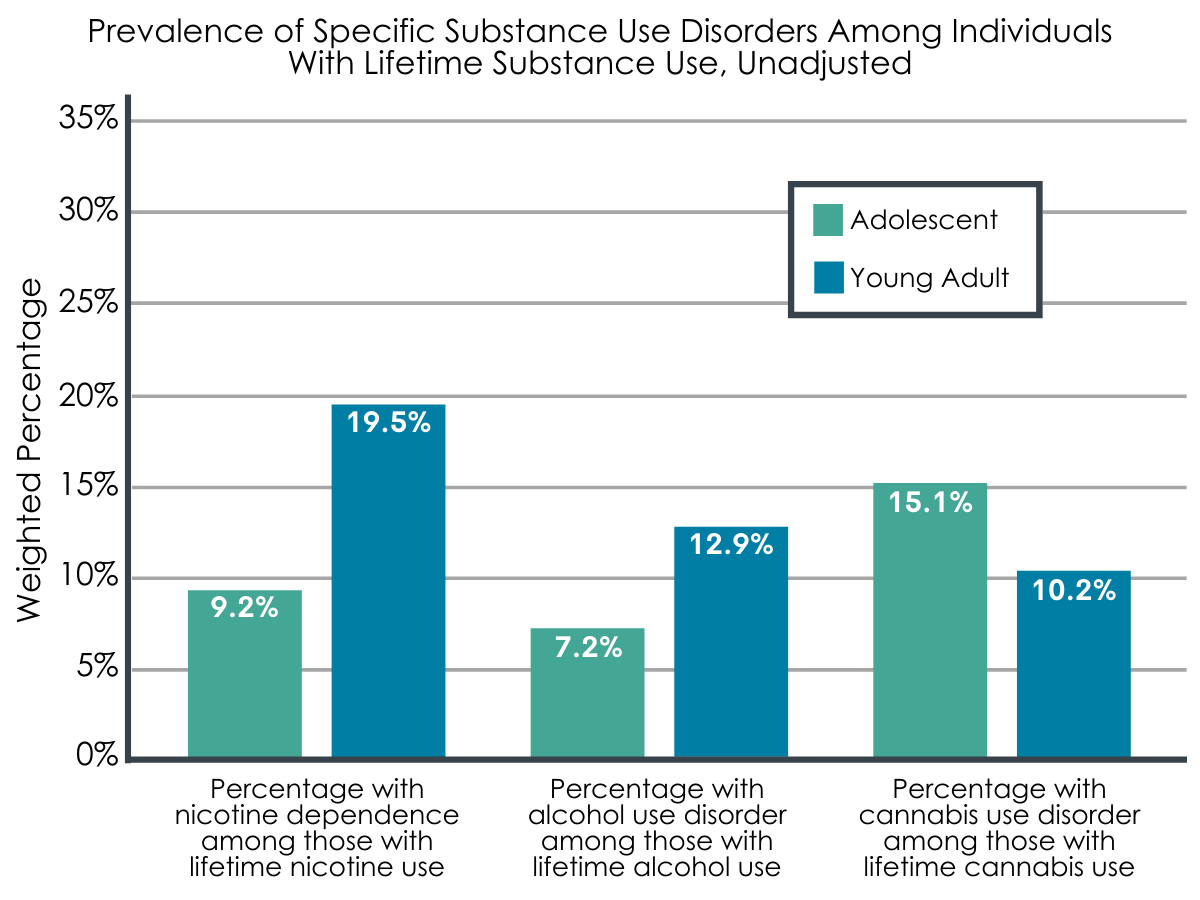

The rate of cannabis use disorder was higher, and the rate of alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence was lower among adolescents compared with young adults.

Figure 1.

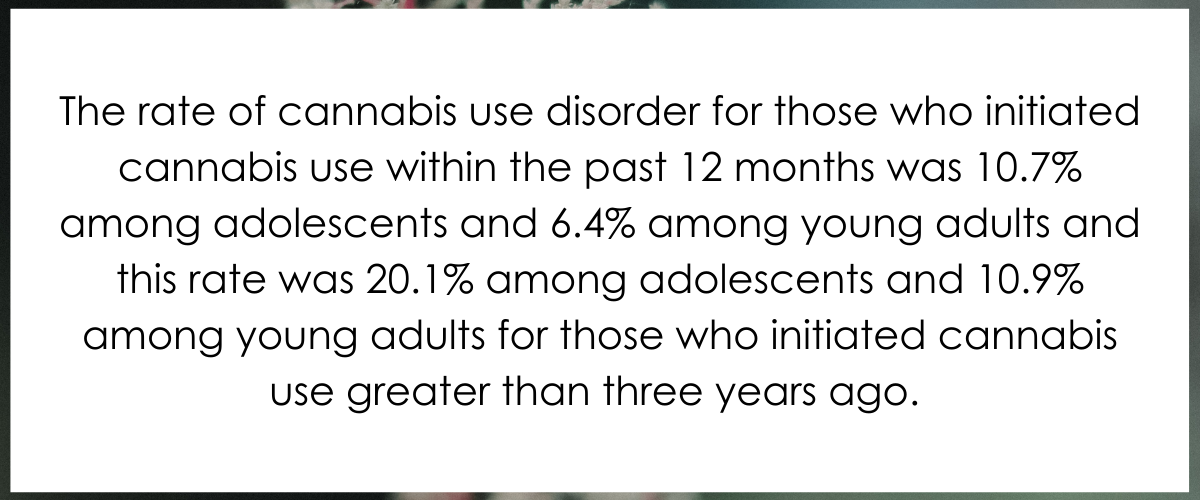

The adjusted prevalence of cannabis use disorder among those with lifetime cannabis use was consistently higher for adolescents compared with young adults across all four time periods. For example, the rate of cannabis use disorder for those who initiated cannabis use within the past 12 months was 10.7% among adolescents and 6.4% among young adults and this rate was 20.1% among adolescents and 10.9% among young adults for those who initiated cannabis use greater than three years ago. On the contrary, the prevalence of alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence among those with lifetime alcohol use or tobacco use was consistently higher among young adults compared with adolescents for the individuals reporting more than 12 months since alcohol or tobacco initiation. For example, the rate of alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence for those who initiated alcohol or tobacco use greater than 24 months but less than 36 months ago was 10.9% and 14.1% respectively among young adults, and 7.9% and 11.6% respectively among adolescents. This rate was 14.2% and 22.2% among young adults and 9.1% and 11.7% among adolescents for those who initiated alcohol or tobacco use greater than three years ago.

Figure 2.

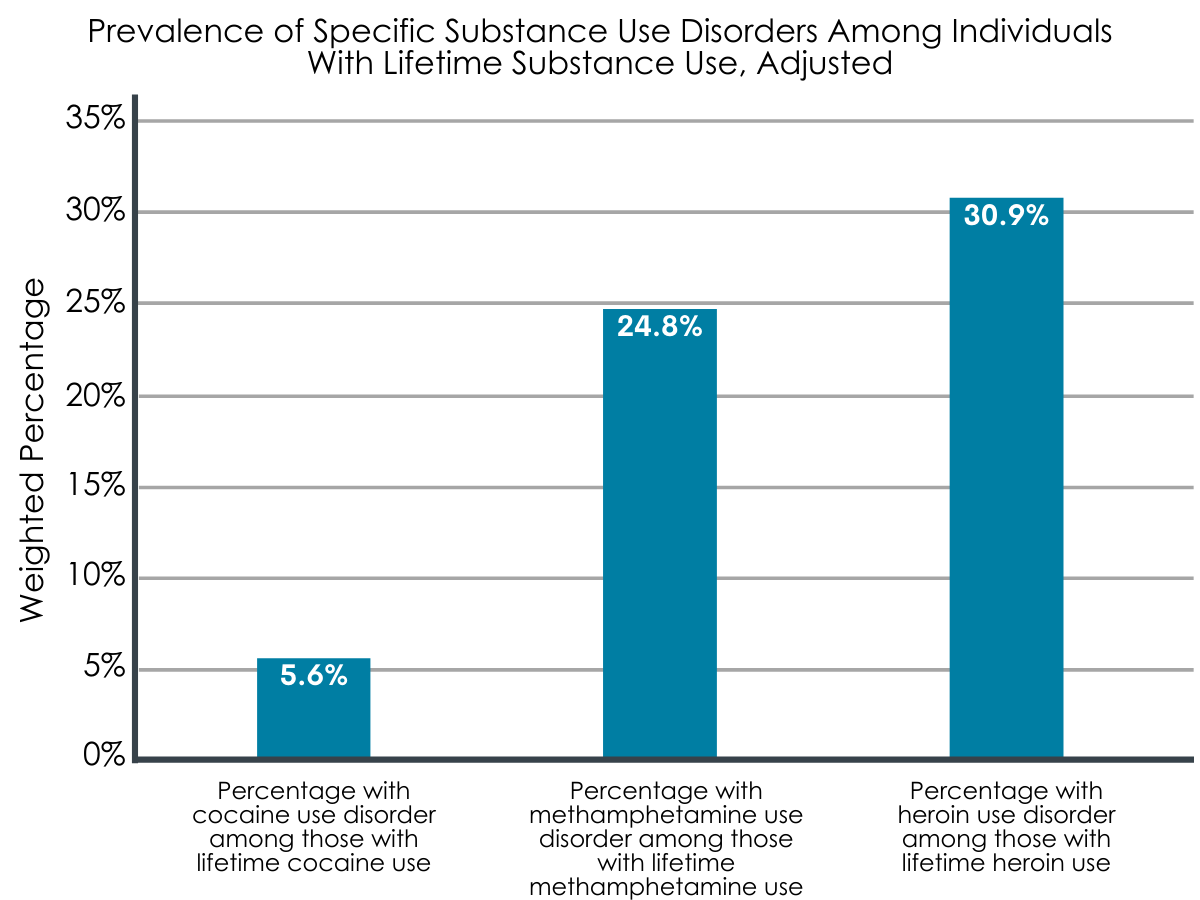

The rate of methamphetamine use disorder and heroin use disorder was high among recent initiates.

Among young adults who reported lifetime use of heroin or methamphetamine, the rate of heroin use disorder and methamphetamine use disorder within 12 months of initiation was 30.9% and 24.8% respectively. However, only 5.6% of those who reported first cocaine use within the past 12 months met criteria for a cocaine use disorder.

Figure 3.

The rate of all forms of prescription drug use disorder were higher among adolescents compared with young adults.

Among young people with lifetime prescription drug misuse, the rate of prescription drug use disorder for prescription opioids, stimulants, and tranquilizers separately was consistently higher for adolescents compared with young adults across all four time periods.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

In this study, the research team found that, among those with lifetime use or misuse, the rate of cannabis use disorder and prescription drug use disorder was consistently higher among adolescents and the rate of alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence was generally higher among young adults. Rates of heroin use disorder and methamphetamine use disorder were high among young adults who initiated use of these substances within the last 12 months.

The findings of this study suggest that only some types of substance use disorders have a faster transition from initiation of substance use for adolescents compared with young adults, highlighting the problematic practice of combining all types of substance use disorders into one measure. Among those with lifetime use, adolescents seem to be more at risk for developing cannabis and prescription drug use disorders whereas young adults seem to be more at risk for developing alcohol use disorder or nicotine dependence. These findings draw into question the role of access and perceptions in substance use. For example, due to legal or economic constraints, adolescents may have limited access to alcohol or tobacco but may have greater access to cannabis or prescription drugs, either through social networks or a parent’s medicine cabinet. This age group may also perceive cannabis use as fashionable and may be further influenced by social norms that encourage cannabis use. On the contrary, young adults would likely not have some of the same legal and economic constraints to access alcohol and tobacco and may perceive alcohol use as fashionable, influenced by social norms (e.g., college). Therefore, initiation and frequency of specific types of substance use may be influenced by access to and perceptions of these substances, ultimately leading to different rates of specific substance use disorders among adolescents and young adults.

Rates of heroin and methamphetamine use disorder were very high among those who had recently initiated use of these substances. Specifically, the rate of heroin use disorder and methamphetamine use disorder within 12 months of initiation was 30.9% and 24.8% respectively among young adults. This is especially concerning given that (across all age-groups) opioid-related overdose deaths accounted for roughly 70% of drug overdose deaths in 2019 and the rate of drug overdose deaths involving psychostimulants (e.g., methamphetamine) has increased six-fold from 2012-2019. Specifically, for those aged 15-24 years old, the drug overdose death rate increased by 20% and the opioid-related overdose death rate increased by 56% from 2006-2015. These stark numbers highlight the importance of prevention, early intervention, and treatment strategies among young adults using these substances. These findings also highlight that the trajectories of initiation of use to problematic use are likely very different based on the substance.

Early onset users are likely to accumulate more exposure to a substance and young people are especially vulnerable to the neurocognitive effects of substances, but mechanisms beyond these factors should be explored in the transition of substance use to substance use disorder. In addition to the role of access and the differences between substances already mentioned, other risk factors are emerging such as adverse childhood experiences and the increasing potency of cannabis. Although these are not able to be captured in the national survey used in this study, further research could use prospective research designs to measure these factors. In addition, this study did not report differences in the rates of specific types of substance use disorders based on sociodemographic factors, which have been documented in previous literature. Future studies should not only control for these factors but examine which ones moderate the relationship between initiation of first substance use and subsequent development of a substance use disorder.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force, whose recommendations drive delivery and payment of preventative services such as screening for substance use, does not recommend screening adolescents for unhealthy drug use or alcohol use in primary care settings, stating that the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. Meanwhile, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening adolescents for unhealthy substance use. The findings for this study show that screening could be beneficial in early identification of problematic substance use, especially among adolescents using cannabis or misusing prescription drugs, although validated screening tools, provider confidence in administering the tool and providing a brief intervention, and appropriate linkage to treatment must be present. Given the vulnerability of adolescents to substance use disorders and the rapid transition of young adults initiating use of heroin or methamphetamine to use disorder, more research in this area is needed to inform clinicians on best practices.