In the United States, there is a large gap between the number of young adults with substance use disorder and the number who engage with specialty addiction treatment. Reasons accounting for the difficulty of engaging this population include both individual barriers (e.g., motivation) and external barriers (e.g., lack of treatment affordability or access). In this study, researchers explored perspectives of recovery among young adults with substance use disorder to better understand some potential ways to reach this population and address barriers to engaging them in treatment and recovery support services.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Engaging and retaining young adults in addiction treatment can be very difficult. In 2019 in the United States, 14% of young adults needed treatment – meaning they met criteria for substance use disorder or received specialty addiction treatment – yet only 1.7% initiated it. As well, research has demonstrated that young adults are less likely than older adults to remain engaged in treatment for the suggested duration. While addiction severity, personal motivation and readiness for treatment are strong indicators of treatment engagement, other research indicates a variety of reasons for the difficulty of engaging this population. For example, there may be internal barriers such as denying that there is a problem, less developed frontal lobes (associated with emotional and behavioral regulation) relative to adults coupled with greater independence than adolescents, interpersonal barriers such as a lack of supportive family or friends (or actively using individuals in their network who provide easy access to substances), or larger system-level barriers such as a lack of treatment affordability or availability. Other studies have indicated that dropping out of treatment is due to feelings of unmanaged cravings, not being able to cope with experiencing negative emotions, or feelings that the treatment was not supportive enough of their particular needs during the process. This study aimed to explore perspectives of recovery among young adults with substance use disorder to better understand some potential ways to reach this population and better address barriers to their engagement with treatment and recovery supports.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study. The researchers conducted in-depth individual interviews (40-70 minutes long) with 20 young adults (21-29 years old) who had current opioid use disorder. The researchers used an interview guide that included open-ended questions covering addiction and recovery, and although they only included patients with opioid use disorder, recovery was discussed as a “whole” rather than specific to their opioid use. The interviews were audio recorded and were then transcribed. The transcriptions were analyzed using an iterative categorization approach, meaning that the researchers read through the interview data several times and created a set of codes. The team used these codes to systematically describe and categorize the interview data. The researchers then further categorized these codes into four overarching themes they felt the data represented.

This sample of 20 young adults who use opioids were recruited from an urban safety net hospital in Massachusetts. The majority were male (65%), Non-Hispanic, Caucasian (75%), and all but one had current or past experience with receiving medication treatment for an opioid use disorder.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

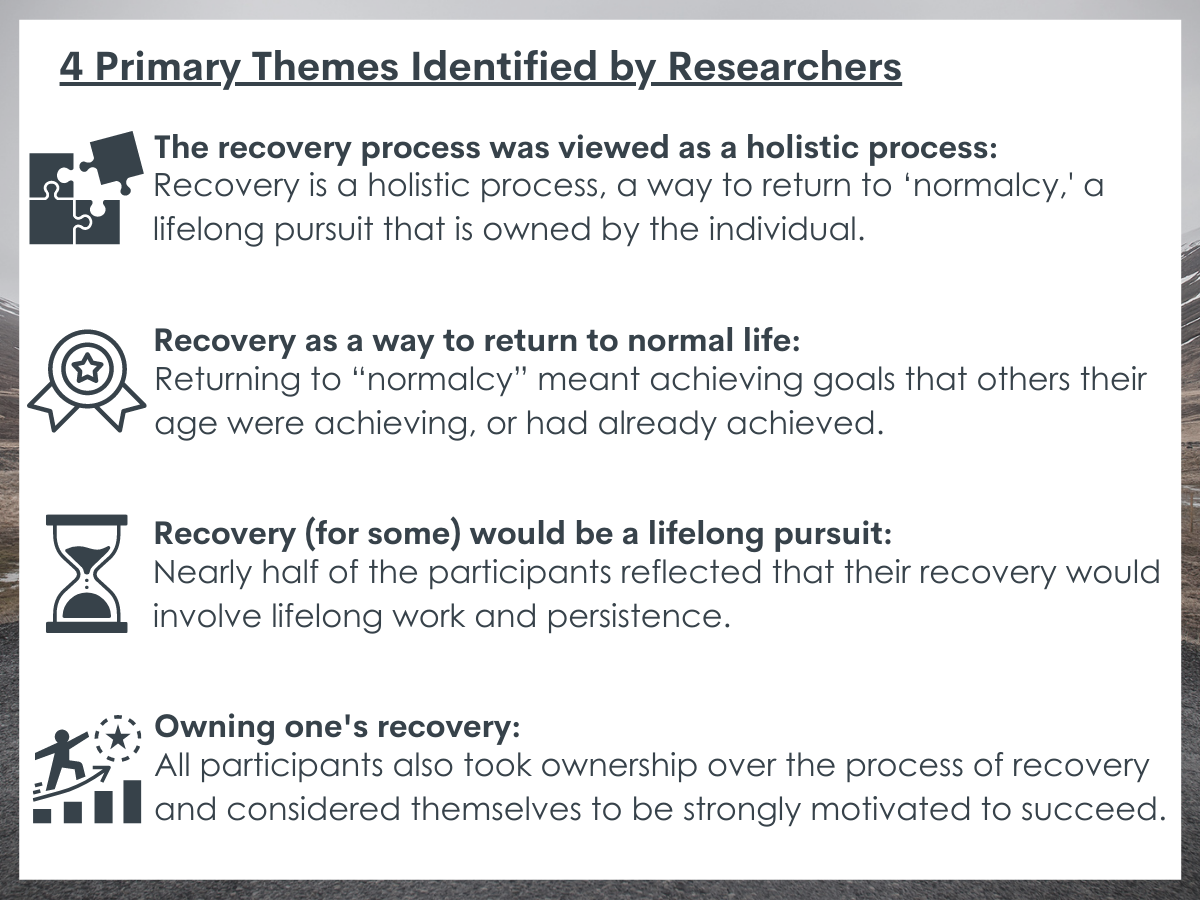

The Recovery Process was viewed as a holistic process.

These young adults described multiple needs that they needed addressed which would require different types of supports and programming in addition to medication treatment and substance use changes. For example, several participants reflected that they needed to engage in mental health services to learn better emotional responses and coping, as well as engage in other activities to enhance their day-to-day lives (e.g., job training, social groups).

“If you utilize everything around you…you’re going to have the most successful chance of getting out of this and making a better life. If you only utilize one, for me, I’ve always struggled. And yeah, it’ll solve one problem in my life but then I still got the other 10 problems.” (Schoenberger, p. 3).

Recovery as a way to return to normal life.

For participants, this return to “normalcy” meant achieving the developmental goals that others their age were achieving, or had already achieved: finding a purpose, pursuing hobbies, finishing school, finding employment, securing stable housing, and finding a partner. It also meant that they wanted to break out of the cycle of substance use cravings driven from their addiction and the resulting negative feelings.

In seeking to find a life outside of substance use, many wanted their identity to be defined not in relation to substances but in light of their other positive achievements. That is, once participants had completed their treatment, some anticipated that they would not want to define themselves as in recovery: that chapter of their life was closed.

“I think the conversation isn’t just about… people won’t die … It’s like people will be present for their lives again.” (Schoenberger, p. 3).

Recovery (for some) would be a lifelong pursuit.

In contrast to the theme of return to normalcy, nearly half of the participants reflected that their recovery would involve lifelong work, a journey in which they would have to remain persistent.

“My recovery…it’s a work in progress. It’s always number one as far as where my life is going. I know my recovery has to remain first in order for anything else to fall into place.” (Schoenberger, p. 4).

Owning one’s recovery.

All participants also took ownership over the process of recovery and considered themselves to be strongly motivated to succeed. For some, hearing that addition is a disease was not helpful as they felt it gave them an excuse not to engage in treatment; they rejected that view and felt they had power over their choice to use and were responsible for that decision. Along these lines, some participants were critical of what they saw as a “recovery cult” presence in some mutual-help groups. That is, they described hearing the same slogans and actions over and over that someone must do to remain in recovery. They felt that simply doing what everyone else in recovery was doing might take away their own agency in the recovery process and their ownership of their own recovery journey.

Selected quotes from study participants.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

This study of 20 young adults engaged in treatment supports findings from existing research which highlight that recovery is a multi-dimensional process, especially for this age group. Recovery for young adults is integrated with the developmental transitions taking place at this time, and so outcomes other than substance use must be considered as markers of success. Importantly, finding a sense of purpose and returning to engage in seeking the developmental achievements of their same-age peers is especially important. Notably, research suggests that this is a reciprocal process of change: as time in recovery lengthens, and milestones are achieved they may grow more committed to their recovery journey and vice versa. Focusing specifically on meeting these milestones may be its own reward for continuing to engage in care.

Along these lines, a developmentally-oriented recovery capital approach suggests that there are a variety of strengths and capacities that a person holds and these can all be used to support their recovery process. That is, there is a need to integrate a focus on identifying life goals and supporting young adults in achieving these goals outside of the addiction recovery space that will help them meet developmental milestones. Thus, any recovery-oriented system of care involved in working with this age group should take a multidimensional approach to address different types of barriers to recovery and to building recovery capital; this approach will likely need to be tailored to some extent to the individual and their unique experience.

Despite the common themes identified by the research team, each participant seemed to view their recovery process slightly differently, which is also in line with existing research. That is, some participants seemed to align strongly with the recovery narrative from 12-step groups which suggested that recovery would be a lifelong process, whereas others felt that narrative had a place for some but was less helpful in their personal process as it removed some of their own agency. This could be due in part to the local 12-step meeting environment: young adults tend to participate in these meetings when there are more similar age peers also in attendance. In some regions, this may not be possible and so to be successful in engaging young adults, there needs to be a wide variety of treatment and recovery services that can work with young adults who have different perspectives on what their recovery journey should look like. As well, these differences suggest that despite the growing body of evidence on recovery pathways and processes, there is still much research to be conducted to better understand different recovery pathways, especially among adolescents and emerging adults.