The opioid use disorder medication, extended-release naltrexone, protects against a return to opioid use. Yet, it is often difficult to initiate and sustain use of medication, especially for youth and young adults. This randomized controlled trial examined whether an intervention consisting of multiple strategies to enhance medication adherence increased receipt of medication and improved opioid use outcomes among young adults after residential treatment.

WHAT PROBLEM DOES THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Empirically-supported medicines can support recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) by increasing an individual’s ability to engage and stay in treatment, protecting against opioid use, and by reducing risk for adverse consequences such as overdose. Individuals with an OUD who remain in treatment and receive the planned dose of medication have better outcomes.

One such medication, extended-release depot injection naltrexone (also known and marketed by the brand name Vivitrol), is considered especially helpful as it reduces barriers to accessing treatment by allowing individuals to make monthly clinic visits (versus daily or weekly). Yet, despite reducing one barrier to access that supports some populations in receiving medication, youth and young adult patients often do not initiate or persist in these treatments. Examining which components of clinical interventions will work to increase treatment retention may also help achieve better recovery outcomes. To address these gaps, this pilot study compared individuals receiving standard care with individuals receiving a multicomponent intervention, comprised of several evidence-based strategies (family treatment, assertive outreach, home delivery, contingency management) to see whether the multicomponent intervention could increase treatment retention and improve substance use outcomes.

Figure 1.

HOW WAS THIS STUDY CONDUCTED?

This was a pilot randomized controlled trial with 41 emerging adults (ages 18-26) diagnosed with opioid use disorder in inpatient treatment at a community substance use disorder treatment center in Baltimore, MD. The study involved randomizing participants interested in receiving medication treatment during outpatient treatment (following their inpatient treatment) to two groups, one which received standard treatment (TAU) and the other which received a multi component intervention (YORS) for 24 weeks. The study aimed to assess differences between the two groups in the number of medication doses received and in return to opioid use. Patients with unstable medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study. Due to study dropout or prolonged incarceration, only 38 participants were included in the analysis.

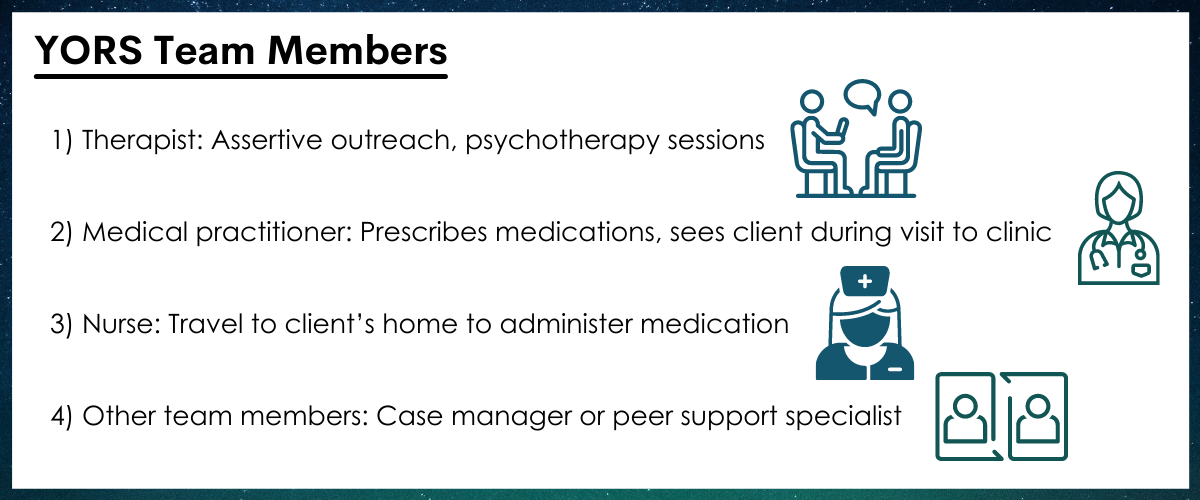

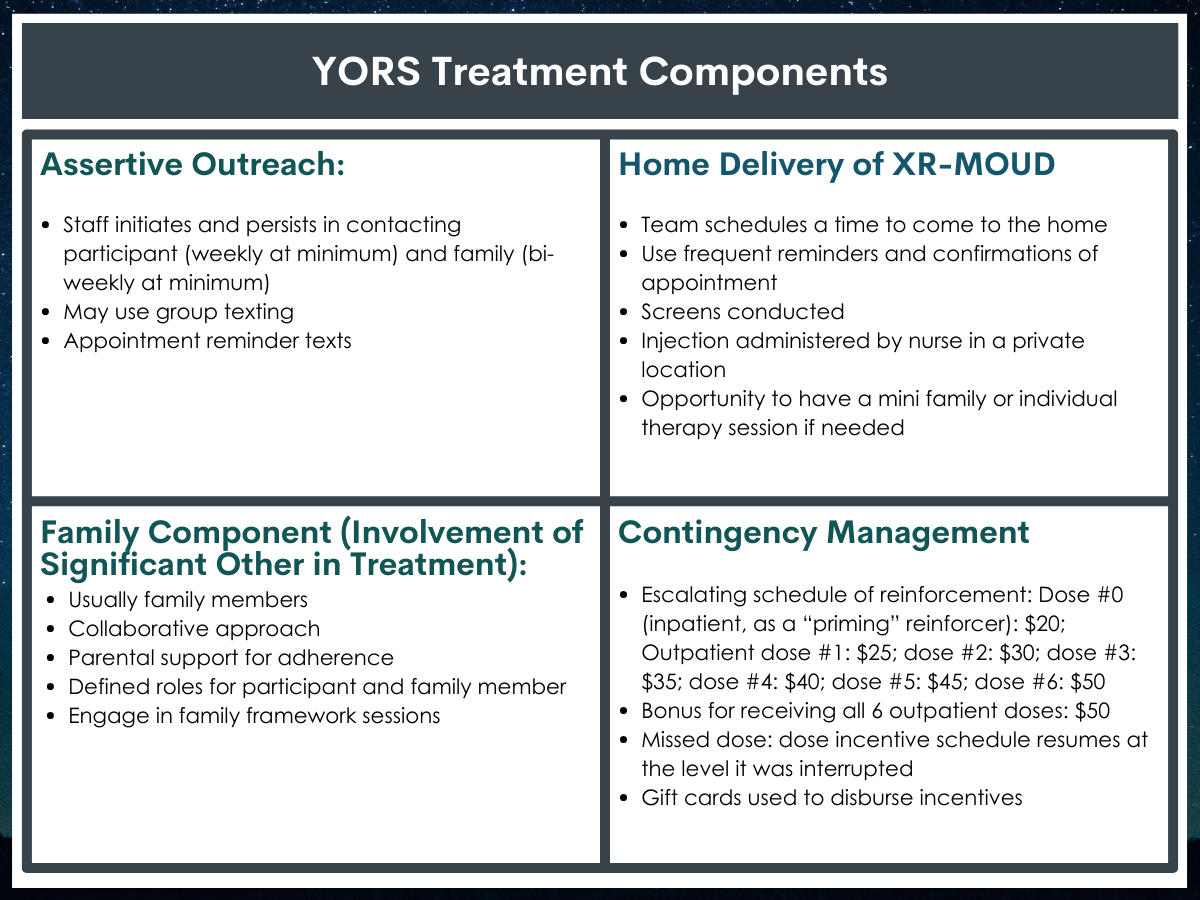

All participants received an initial first dose of extended-release naltrexone before they were discharged from inpatient treatment. The Standard Treatment (TAU) group received standard referrals to continuing substance use disorder care, including extended-release naltrexone received at a doctor’s office. The Intervention (YORS) condition included four parts: (1) Home delivery of medication + counseling, (2) Family component, (3) Contingency management (monetary incentive for each received dose), and (4) Assertive outreach and ongoing contact from treatment providers to the patient and a chosen family member, called a “treatment significant other”. The family component included OUD education, treatment planning, and a written family plan.

Figure 2.

Participants were followed for a 6-month period. During this period, they answered questions on their substance use and provided urine screens every 2 weeks. Treatment service usage data were collected from the clinics. The 2 primary outcomes were the (1) total number of doses received (out of the 7 possible including the dose received at end of inpatient stay) and (2) relapse to opioid use over 24 weeks. A relapse to use was considered use of opioids for 10 or more days within a 4-week period. Each missing or positive urine screen was entered as positive for 5 days of opioid use per each 2-week period. Other outcomes the authors examined included the number of days of opioid use, opioid abstinence, other substance use, and readmittance to treatment.

This study sample included 41(38 participants were eligible and included in the analysis) emerging adults in Baltimore, MD, who were seeking treatment for OUD; on average participants were 23 years of age; roughly two-thirds were male (65%) and most were on Medicaid (84%). The majority of participants designated a parent (81%) as their treatment significant other, while the remaining had other family members, a romantic partner, or sponsor/mentor.

WHAT DID THIS STUDY FIND?

Intervention participants had higher levels of treatment engagement compared to standard treatment.

Participants in the intervention group (YORS) received 4.3 doses of medication whereas those in the standard treatment group (TAU) only received 0.70 (i.e., less than 1 dose per participant, on average).

Participants in the intervention group (YORS) remained in outpatient treatment for a median (i.e., 50th percentile) of 9 weeks whereas those in the standard treatment group (TAU) remained in outpatient treatment for only 3 weeks. These findings indicate that only participants in the intervention (YORS) group were likely to continue in outpatient treatment until (and following) their second dose of medication.

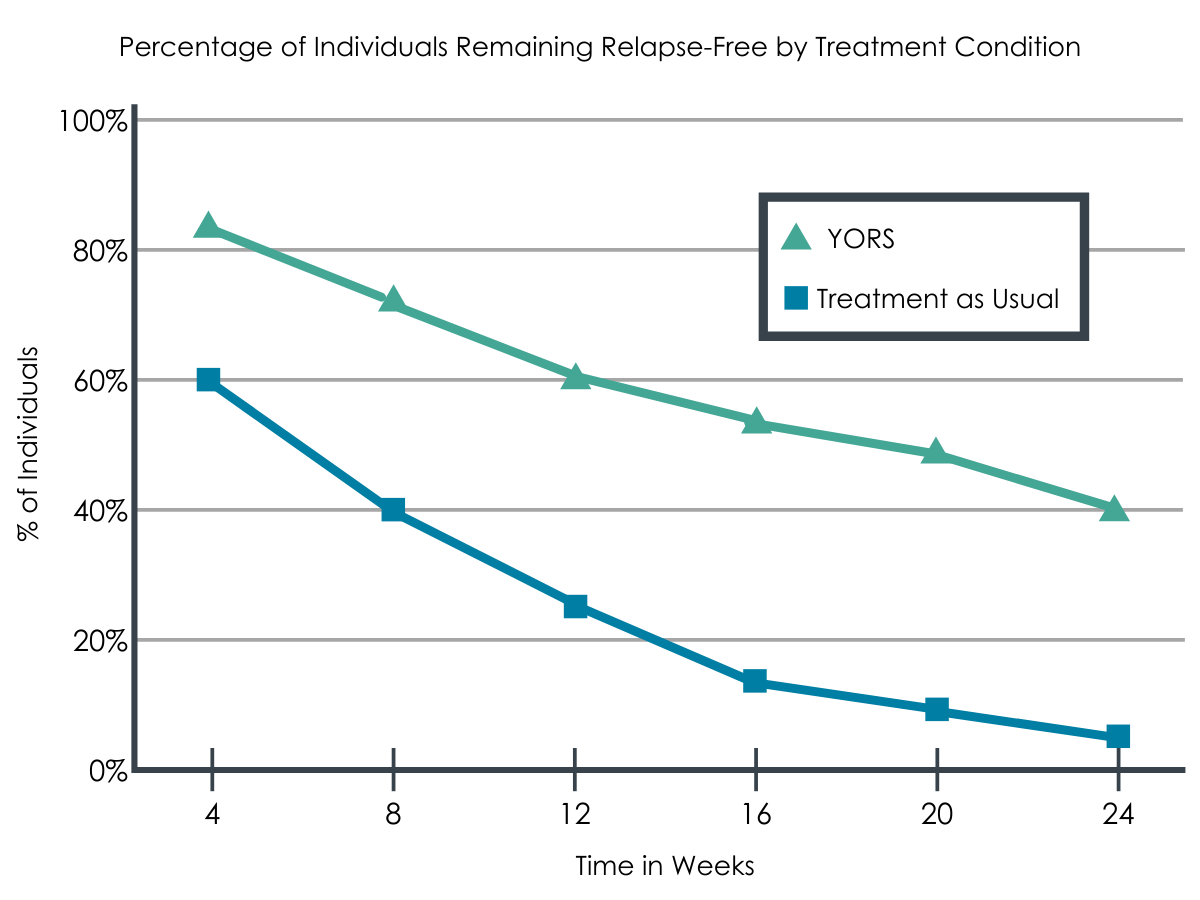

Intervention participants had lower return to opioid use rates at 24 weeks than standard treatment participants, but levels of abstinence did not differ between groups.

Intervention (YORS) participants were significantly less likely to relapse (i.e., use of opioids for 10 or more days within a 4-week period) than standard treatment (TAU) participants: 61% versus 95%.

Figure 3.

Overall, as medication use increased, opioid relapse and overall days of use decreased, yet there were no differences between the groups in time to first opioid use or in rates of complete opioid abstinence over the course of the entire 24-week follow-up. Only 1 participant stayed completely abstinent until 24 weeks.

1/3 were readmitted to inpatient treatment.

About 37% of participants were readmitted to inpatient treatment during the study, although this did not significantly differ between the two groups (9 YORS, 5 TAU).

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY FINDINGS?

Through this study, the researchers demonstrated that the multicomponent intervention, which included home delivery of medication and counseling, a family component, contingency management, and assertive outreach resulted in significantly more medication doses than standard treatment. As well, members of this multicomponent group were retained in treatment longer and had a significantly lower rate of return to opioids during the course of the study. These findings support the approach of offering young adults a comprehensive and diverse set of outpatient supports after an initial bout of inpatient treatment: Incorporating significant others, such as family, may be a key component to success in a multi-component intervention. Although the study cannot address which of these supports were most effective, the intervention components are all based on existing evidence; together, they may work in a way to build recovery capital that sole-component interventions may not be able to do. While this is an encouraging effect, the intervention approach was resource-intensive, and it is unclear the extent to which programs may be able to implement the intervention package in standard treatment. That said, if these effects are replicated in larger samples and are shown to be cost-effective, the extra effort involved could yield important recovery dividends for emerging adults.

Approximately 1/3 of participants returned to inpatient treatment during the study, following typical cycles of recovery among this age group and among those who use opioids; the authors suggest that the multicomponent group was more easily and quickly identified for a return to treatment, but this perception should be confirmed in additional, larger, studies of the intervention.

Despite these promising findings only one participant remained abstinent during the trial, suggesting further research into other barriers and facilitators for this age group may be necessary. Indeed, this is similar to other research, which suggests that the use of extended-release naltrexone does not work for everyone. As well, it is important to note that while extended-release naltrexone may be easier to adhere to for participants given it only requires a monthly dose, only its alternative, buprenorphine, is associated with reduced overdose risk.